There are parallels to be drawn between the Wu-Tang Clan’s incorporation of Chinese martial arts films and Edward Said’s analysis of Jane Austen’s novel Mansfield Park, Jane Austen and Empire. More specifically, we must compare the Wu-Tang Clan’s treatment of the film to Austen’s treatment of Antigua. The comparison reveals that both the Wu-Tang Clan and Austen are guilty of exploiting foreign ideas and cultures in their art — for better or worse.

We must look at the sense of morality employed by the Wu-Tang Clan and Austen respectively. Said contends that Austen views Antigua as an entity that is “‘out there’ that frames the genuinely important action here, but not for a great significance” (1122). Said is alluding to a sort of disrespect here, arguing that Austen is using Antigua inappropriately. He is essentially saying that Austen is compounding the view that the island merely symbolizes Bertrams’ drive for property and wealth without playing an actually significant, telling role within the plot. It is tempting to make a similar conclusion concerning the Wu-Tang Clan’s use of Chinese martial arts films – is the rap group’s use of audio clips from the films enough to show proper appreciation, rather than wrongful appropriation?

The Wu-Tang Clan’s entrance into the rap scene was explosive and remarkable, to say the least. With the release of their first album, Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), the group showcased all of its unique, appealing personalities through hard-hitting vocals and memorable lyricism. It was a winning combination, with the group from New York building upon the strong foundation they received from the album’s critical success to become one of the most legendary rap groups in history.

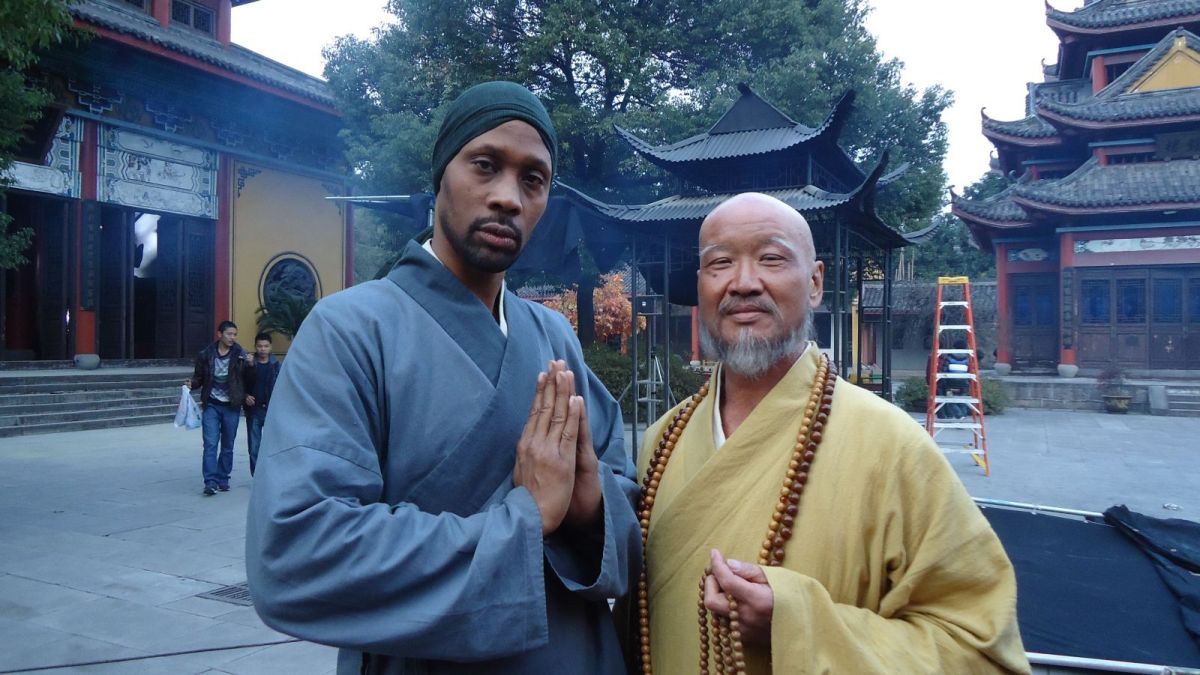

But a big part of the album’s success was its heavy incorporation of Chinese martial arts films. Even the title of the album is a reference to the 1978 movie The 36th Chamber of Shaolin. This was a new feature to say the least – mainstream rappers had never before looked to east Asian influences to include in their music. (Though this nuance appeared less frequently in the group’s later work, one member of the Wu-Tang Clan, RZA, directed his own martial arts film based in China, in 2012: The Man with the Iron Fists.)

Each song on Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) incorporates some sort of element from a Chinese martial arts movie. For example, the introductory song begins with a few words of speech from the 1983 film Shaolin and Wu Tang (hence the group’s title, Wu-Tang Clan):

The words, exactly, are:

“Shaolin shadowboxing and the Wu-Tang sword style. If what you say is true, the Shaolin and the Wu-Tang could be dangerous. Do you think your Wu-Tang sword can defeat me?”

“En garde, I’ll let you try my Wu-Tang style.”

The speech here is well used. It sets a violent, in-your-face tone; what follows are gruesome lyrics over an abrasive instrumental, as group member RZA urges listeners to “Bring da motherfucking ruckus”.

Take the seventh track on the album, “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthing ta Fuck Wit” for example, too. The first words heard on it come from the 1977 Chinese martial arts film Executioners from Shaolin: “Tiger Style!” This is a reference to a fighting technique. Again, the matching aggressiveness that follows is obvious – just look at the track’s title. RZA, in this instance, goes on to instruct fellow group member Method Man: “Hah! Lebonon, step up, boy! Represent! Chop his head off, kid!”

The Wu-Tang Clan, with their first album, knew they only had one coming-out party. They wanted to be ‘out there’ and give the rap scene (at least New York City’s) a product that was never experienced before. They went about doing this by being ultra-aggressive, and introducing this style with confrontational, violent words from Chinese martial arts films. They could have used an endless amount of quotes from American films, but looking to a place as far away as China for such inspiration was never done before. It was another note of uniqueness, and it worked marvellously. The album sold, and was received extremely well.

All that said, it is not known which came first: the Wu-Tang Clan’s obsession with Chinese martial arts films, or their aggressive music? If the aggressive music resulted from their obsession to recreate the tone from these films that they enjoyed, then I would consider that rightful appreciation. If they were aggressive to begin with and merely tacked on the quotes from the films to add an exotic feature, then that would constitute wrongful appropriation.

There is some serious grey area here – we do not know if their intentions came from a place of genuine admiration. As aforementioned, RZA went on to direct a martial arts film but the Wu-Tang Clan’s incorporation of Chinese martial arts films subsequently decreased. The violent words of Shaolin fighters made rather more erratic appearances in their discography following the release of Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers).

The thin line between proper appreciation and wrongful appropriation continues to exist in the hip-hop industry today. The Wu-Tang Clan were not the first to call upon an earlier time to influence their music – it is believed that rappers’ diss tracks (in which they purposefully insult and degrade other rappers) originated from the popular, playful game “the Dozens”, which involved individuals from impoverished Black communities trading insults until one quit and a winner emerged. More recently, the now renowned Drake has attracted controversy for his covers of songs “Sweeterman” and “Ojuelegba”. In both, he speaks patois, the Jamaican slang language, though he has no Jamaican heritage. Moreover, the song “Ojuelegba” is actually Nigerian in origin.

Clearly, the conversation is there to be held in the present day, as well.

Works Cited

Said, Edward. “Jane Austen and Empire.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Ed. Rivkin, Julie and Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004.

Great post, Fares! You did a great job drawing an example that I never would have thought of. I’ve never listened to Wu-Tang before, but I definitely agree with your points. My guess is that without the Chinese influence, Wu-Tang wouldn’t have nearly the success he does today. Applying Said and even Kincaid to art and music is an interest conversation. When I think of art, I think of appreciation and expression. However, when that expression and appreciation is drawn from another culture, where is the line drawn between imitation, disrespect, exploitation, and admiration? Does the art form turn into a mockery of the culture? Lots of unanswered questions to discuss. I really enjoyed the read. Thanks, Fares!

LikeLike

I think there is something that is not talked about a lot in the appreciation or appropriation debate. It relates to the childhood experiences of these rappers. I know that Drake lived in a part of Toronto that had a large number of Jamaican immigrants. I assume that the members of the Wu-Tang clan grew up watching these martial arts movies as both were released roughly fifteen years before their debut album. I don’t think that this is a consciousness appropriation. They grew up with these cultures, it is to be expected that the cultures will have some sort of presence within their lives and their works. The question then is that if we consider the experiences of these rappers, where do we draw the line between appreciation and appropriation? Iggy Azalea is someone who is widely criticized for appropriating black culture. But she could very well say that she grew up listening to rap and watching rap videos. It seems to me that there is no brightline to distinguish the two, something that you also conclude.

LikeLike

Camron, you raise a good point here.

Is it enough to merely be exposed to the culture in your upbringing when are you attempting to incorporate its influences in your own art? In short, I do not know, but I am tempted to say that it at least helps.

I wonder how the Jamaicans that Drake encountered and grew up generally feel about him using their slang language. Do they take offence? Or do they appreciate seeing their heritage appear in popular music and obtain more attention?

And for, Iggy Azalea, I think the grey area is even more serious there. In terms of her case, Black rappers have actually stepped up and spoken out against her involvement in the hip-hop industry. The legendary Erykah Badu only last week called what Iggy Azalea was doing “not rap”. Who makes the call here about whether or not Azalea is engaging in proper appreciation or disrespectful appropriation? The public or the genre’s authorities?

In my comment on Michael’s post, I brought up Yung Lean. What do we make of him, for that matter? Surely, yes, he was brought up exposed to Asian culture, as he played Pokémon and must have had a few other hobbies that originated from that area. But, to me, he seems to be employing Asian culture ‘too’ much, and it’s overkill. So, we must consider balance too.

For what it’s worth, I think the Wu-Tang Clan struck the right balance.

LikeLike