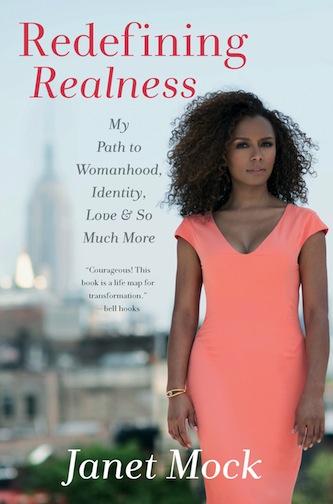

Judith Butler’s careful consideration of trans individuals in relation to her theory of gender as an “act” brings me to the case of Janet Mock, a prominent trans woman who has garnered renown for her revealing, enlightening autobiography Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More (though I must add that she is acclaimed for being a distinguished journalist in her own right, before her autobiography was released). In considering Mock, we must consider Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s views on “male homosocial desire”, which she says is “the radically disrupted continuum in our society between sexual and nonsexual male bonds” (709). The radical disruption that Sedgwick speaks of is caused by homophobia, as individuals engage in it to disrupt male bonds and maintain a patriarchy governed by heterosexual men. We must also consider Judith Butler’s main argument, the crux of which is this: “Gender reality is performative which means, quite simply, that it is real only to the extent that it is performed” (907). Gender is, according to Butler, an “act” (908). One is not merely a man or a woman but acts as either role to define their own gender. Mock’s experience as a trans woman reinforces Butler’s theory of gender through performance and appearance, and counters Sedgwick’s beliefs concerning the use of homophobia against strictly “male homosocial behavior”, as she finds her own ways to act as a woman and must fight against homophobia in her efforts to engage in female homosocial behavior.

Butler’s theory brings forward interesting intricacies concerning trans individuals, and she recognizes this: “Indeed, the transvestite’s gender is as fully real as anyone whose performance complies with social expectations” (907). Mock, for a long period of time, struggled to fully express her trans identity and find the best, most complete way to “act” her gender. This is best exemplified by her initial forays into the dating world, when she was dealing with the fine line concerning her appearance and the truth that she was attempting to conceal. In her autobiography, Mock details her first date with Adrian, a man whose “lustful gaze… further validated my womanhood” (158). The date was a nervous affair for Mock, at least initially: “But as dinner progressed, my nerves subsided, and I fell into the groove of a girl on a date with a guy” (158). Therefore, we can see that “acting” a gender has much to do with environment and company. The quality of these conditions determine how the individual can best express their gender. This is reinforced by the fact that Mock’s definition of womanhood is derived from “watching the women in Dad’s life cook and cackle in the kitchen” (65).

As Mock’s life goes on, she embraces more apparent ways of expressing her movement across genders, as she starts a hormone treatment and begins dressing in a more feminine manner. She practically outright supports Butler’s theory concerning the importance of “acting” a gender, especially through her appearance: “I clutched tightly to my green Keroppi folders and my size-too-small jeans and my arched brows, and when I could grow my hair long enough, my side part. These elements, though small and insignificant to passersby, made up my girlhood, and I fought hard to ensure that they were seen” (124).

Mock’s emergence and eventual coming to comfort and normality as a woman was undermined by homophobia. Sedgwick argues that homophobia is used to balance and combat the “male homosocial desire”. In Mock’s case, however, she encounters homophobia in her efforts to engage with the “female homosocial desire”, as she wants to be a woman among women (709). This struggle is compounded by Mock’s father’s initial reaction to her exploring her gender identity, as he abandons his daughter and dismisses her life journey, saying that he would not support it. (He eventually comes around to reaffirm his unconditional love for Mock). Mock’s experience with her father speaks volumes of Sedgwick’s belief that “patriarchies structurally include homophobia”, if we are considering her father as a one-man patriarchy (698). How do you think Mock herself would interpret Sedgwick’s key theory concerning homophobia’s role against homosocial desire? She would obviously read Sedgwick’s work with great intrigue, to say the least.

Mock would read Butler’s work with intrigue, too. “My point is simply that one way in which this system of compulsory heterosexuality is reproduced and concealed is through the cultivation of bodies into discrete sexes with ‘natural’ appearances and ‘natural’ heterosexual dispositions,” Butler writes (905). Mock agrees with Butler’s statement here, as she has felt automatically maligned by greater society for changing her bodies from its “natural” appearances to fulfill her non-heterosexual (and therefore non-“natural”) sexual desires. “It was a balancing act to express my femininity in a world that is hostile toward it and frames femininity as artifice and fake, in opposition to masculinity, which often represents ‘realness,’” Mock writes (124). What it would take for trans individuals to have their bodies and sexualities be defined as ‘natural’? Will it take a formal deconstruction of the word ‘natural’, or what it means?

I think that you are misusing the term homophobia to describe the experiences of Mock. A much better term would be transphobia. Sedgwick does not talk in depth about trans people in the reading and I don’t think she would agree that trans people face homophobia and homosocial desire. There is an important distinction that needs to be made between the two. I would argue that trans bodies are always excluded from systems within our society as they can never truly experience homosocial desire. A trans man will not experience homosocial desire within a patriarchal system which excludes trans bodies as transphobia is an over-determining factor. In other words, a trans man can never become a member of the patriarchy. Additionally, I think that transphobia is a much more violent form of oppression than homophobia. I mean this in terms of actual violence, microaggressions, and how society is built to inherently exclude trans bodies. This is especially true today where we have an unprecedented era of trans visibility and a notable backlash to trans people. This is a marked contrast in compared to homosexual people. They are now a part of the dominant systems in our society (think the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell). While homosexual people still experience oppression by the patriarchy, they are in some way included within it while trans people will be excluded for the foreseeable future.

LikeLike

I think I have to hold my hands up here and plead ignorance. You are absolutely right – transphobia is not the same as homophobia. However, as Patrizio has brought up, Mock certainly encounters homophobia in earlier years, before she makes her movement across genders more apparent.

Also, I would disagree with your belief that trans individuals cannot express homosocial desire – surely they could want to spend more time with people whose gender they have become personally accustomed to, whose gender they have embodied?

And transphobia is not necessarily always expressed more violently than homophobia. It has subtle forms of expression too, such as bathrooms that may not be entirely welcoming or inclusive of trans people. They receive this form of oppression from the patriarchy, so I believe that they must be part of the system that is governed by this patriarchy.

LikeLike

I think it’s important to remember that, once Mock self-identified as a woman, she is no longer a homosexual. Though she may have struggled with it at the beginning (and you’ll have to inform us as to the extent), a trans person questions his or her own gender, gather than the gender of the romantic/sexual partner. Though these issues are certainly related, and I’m sure Mock has experienced a number of different phobias, we might risk discounting her self-identification as a heterosexual woman if we privilege homophobia above transphobia after her transition.

LikeLike

Fares – truly meticulous treatment of a complex subject. Regardless of my thoughts on the concepts themselves, I definitely followed your logic and thought your comparisons to the theory we have read in class were on point and intriguing. In contrast to Camron’s note about your use of the word homophobia, I think it is appropriately used. Keeping in mind that I had not heard of Mock before your article, it sounds like in the time frames in which you describe Mock’s struggles, Mock has not yet become fully trans, so I feel that social pressure Mock would have felt from that would have been homophobia, as the slight adjustments Mock describes early on would probably be perceived more as “gay tendencies” than full on “trans behavior”, because, as Camron notes, trans is definitely less accepted in today’s culture relative to homosexuality.

Furthermore, the concept of a man performing as a transexual female definitely is a great case study on Butler’s gender performance theory.

Finally, I thought that the stuff you brought in about Mock’s feelings on the first date were really interesting. I feel that what you noted about how “acting a gender has much to do with environment and company” can be said about all gender performances… I would imagine that a naturally born and “performing” female could potentially feel the same self-consciousness on a date as could a naturally born and “performing” male, as well as any person who identifies anywhere in between. (Although its not binary 🙂 ).

Great post man! See you tomorrow.

LikeLike